‘They were recruited because of their womanhood’

Interview with law alumna and author Sophie Poldermans

17 October 2023

‘Poldermans is pleased that there is increasing attention to women in resistance during World War II. 'Very often the emphasis was on armed and male resistance. While many women, for example, did courier work or took Jewish children to hiding addresses. That was often not seen as resistance.'

Her interest in Hannie Schaft begins with Harry Mulisch's The Assault. At 15, Poldermans read the book, which was partly based on Hannie's story. 'I was also a teenager and grew up in the same city, Haarlem.' Wars fascinate her. 'People are apparently capable of doing horrible things to each other. It made me think about justice and human rights.'

In secondary school, Poldermans makes a school assignment about Hannie Schaft for the History course. Through the network of her father, who was Haarlem's city archaeologist, she discovers that Truus Oversteegen is still alive. She was a fellow resistance member of Schaft. 'I called her. Truus was a wonderful woman, with an approachable, warm personality. But she did shoot people once.' Truus sees how seriously Sophie is working on the paper and introduces her to her sister Freddie. 'Hannie, Truus and Freddie were a kind of trinity within the Dutch armed resistance,' Poldermans explains. 'She asked me to speak at the National Hannie Schaft Commemoration in a packed church with hundreds of people. I was barely 17 at the time.'

Human Rights

After a year attending high school in the United States, Poldermans chooses to study Dutch law and International Law at the University of Amsterdam. She describes the law programme as interesting, but also very broad. There were only 2 courses on human rights. 'Yet I immediately knew: this is it. That has shaped me to this day. I'm still working on human rights.'

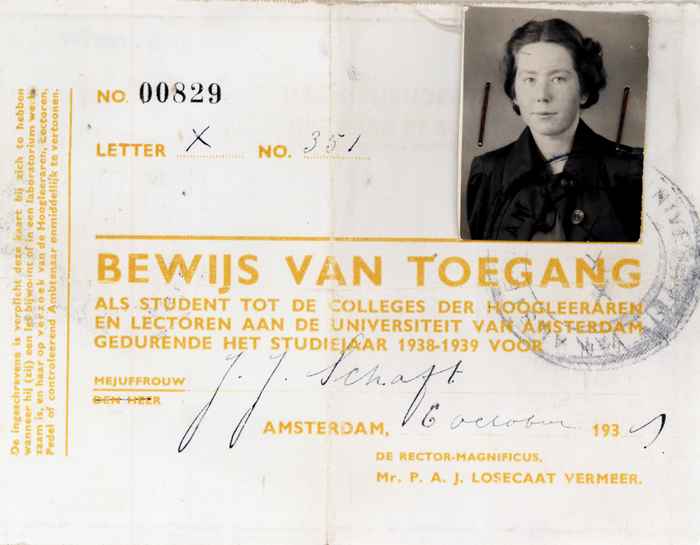

Poldermans thinks her choice of study is very much shaped by Hannie's history and the conversations she had with Truus and Freddie. 'Hannie Schaft also studied law at the UvA. She dreamed of going to Geneva to work at the League of Nations, the forerunner of the United Nations.' At Truus' request, Poldermans joined the board of the National Hannie Schaft Foundation at the beginning of her studies. 'I have done that for over 10 years with both sisters.'

Women in a leadership role

To draw attention to the role of women in times of conflict, Poldermans began as an independent in 2019. 'Women are often portrayed as victims. But it is precisely women who are strong leaders in times of crisis and conflict, according to a major Harvard Business Review study. I myself saw this during research in Rwanda, Kosovo and Yugoslavia, but Hannie, Truus and Freddie have also shown this.' According to Poldermans, today, from Afghanistan to Iran, you see women being a hub of resistance.

She recognises the same patterns she encounters in the story of Hannie, Truus and Freddie. It was unusual for women to join the armed resistance during World War II. 'At the beginning of the war, Hannie was 19, Truus 16 and Freddie 14 years old. They were recruited specifically because of their womanhood. They stood out less and could use their youthful beauty as a weapon of war. They went on missions dolled up to get information from the enemy while flirting. They even lured senior officers into the forest to kill them.'

A Dutch edition

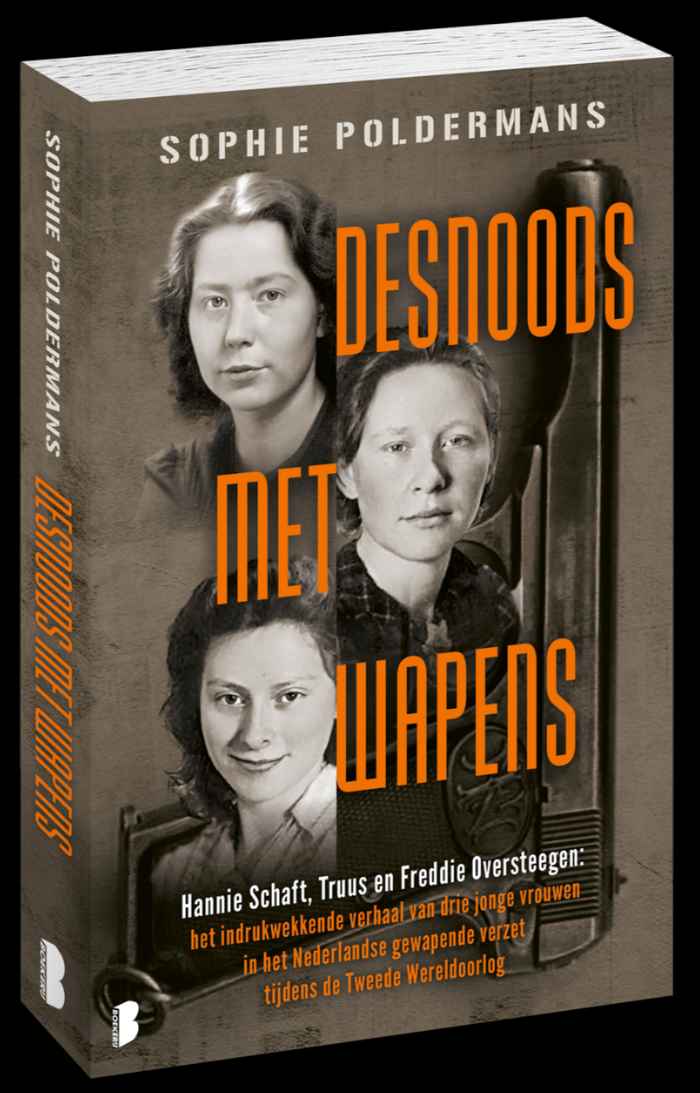

Shortly after Poldermans started for herself, Freddie died as the last of the three resistance comrades. A Washington Post journalist approached her for information to write an obituary, as hardly any English-language information was available. 'That obituary went viral. Suddenly a lot of attention came to the story of Hannie, Truus and Freddie.' Poldermans had always wanted to write a book in English about them. 'This was the moment. I independently published the book Seducing and Killing Nazis.' After the New York Post interviewed her, the book sold like hotcakes. 'A world opened up for me because the book was so well received.' However, the Dutch version, Desnoods met wapens (With weapons if necessary), became a very different book. 'Seducing and Killing Nazis is a factual, historical account. The Dutch book is more comprehensive. I interviewed more people for it. At the publisher's request, it is written narratively, from the women's perspective.'

According to Poldermans, it is not known how many people were liquidated by the women. 'They never wanted to tell. Of course, they were not cut out for shooting either. They were young girls.' With the book, the author wants to show precisely how much it cost them. 'Hannie ended up paying for it with her life. She was depressed before that, and the Oversteegen sisters were severely traumatised by the events.'

Discrimination and exclusion

Asked why it is so important to tell the story, Poldermans replied that, firstly, the story is unique. To her knowledge, there were only about 6 women in the armed resistance in the Netherlands. Secondly, the generation that experienced this war is dying out. 'I want the stories to be passed on. For young people, the Second World War seems a long time ago. But the stories are about discrimination and exclusion. This still happens every day in the workplace and at school. I think it's important that you can get a positive message out of a horrific event: dare to stand up for someone else.'